7. Releasing and versioning#

Previous chapters have focused on how to develop a Python package from scratch by creating the Python source code, developing a testing framework, writing documentation, and then releasing it online via PyPI (if desired). This chapter now describes the next step in the packaging workflow — updating your package!

At any given time, your package’s users (including you) will install a particular version of your package in a project. If you change the package’s source code, their code could potentially break (imagine you change a module name, or remove a function argument a user was using). To solve this problem, developers assign a unique version number to each unique state of their package and release each new version independently. Most of the time, users will want to use the most up-to-date version of your package, but sometimes, they’ll need to use an older version that is compatible with their project. Releasing versions is also an important way of communicating to your users that your package has changed (e.g., bugs have been fixed, new features have been added, etc.).

In this chapter, we’ll walk through the process of creating and releasing new versions of your Python package.

7.1. Version numbering#

Versioning is the process of adding unique identifiers to different versions of your package. The unique identifier you use may be name-based or number-based, but most Python packages use semantic versioning. In semantic versioning, a version number consists of three integers A.B.C, where A is the “major” version, B is the “minor” version, and C is the “patch” version. The first version of a software usually starts at 0.1.0 and increments from there. We call an increment a “bump”, and it consists of adding 1 to either the major, minor, or patch identifier as follows:

Patch release (0.1.0 -> 0.1.1): patch releases are typically used for bug fixes, which are backward compatible. Backward compatibility refers to the compatibility of your package with previous versions of itself. For example, if a user was using v0.1.0 of your package, they should be able to upgrade to v0.1.1 and have any code they previously wrote still work. It’s fine to have so many patch releases that you need to use two digits (e.g., 0.1.27).

Minor release (0.1.0 -> 0.2.0): a minor release typically includes larger bug fixes or new features that are backward compatible, for example, the addition of a new function. It’s fine to have so many minor releases that you need to use two digits (e.g., 0.13.0).

Major release (0.1.0 -> 1.0.0): release 1.0.0 is typically used for the first stable release of your package. After that, major releases are made for changes that are not backward compatible and may affect many users. Changes that are not backward compatible are called “breaking changes”. For example, changing the name of one of the modules in your package would be a breaking change; if users upgraded to your new package, any code they’d written using the old module name would no longer work, and they would have to change it.

Most of the time, you’ll be making patch and minor releases. We’ll discuss major releases, breaking changes, and how to deprecate package functionality (i.e., remove it) more in Section 7.5.

Even with the guidelines above, versioning a package can be a little subjective and requires you to use your best judgment. For example, small packages might make a patch release for each individual bug fixed or a minor release for each new feature added. In contrast, larger packages will often group multiple bug fixes into a single patch release or multiple features into a single minor release, because making a release for every individual change would result in an overwhelming and confusing amount of releases! Table 7.1 shows some practical examples of major, minor, and patch releases made for the Python software itself. To formalize the circumstances under which different kinds of releases should be made, some developers create a “version policy” document for their package; the pandas version policy is a good example of this.

Release Type |

Version Bump |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Major |

2.X.X -> 3.0.0 (December, 2008) |

This release included breaking changes, e.g., |

Minor |

3.8.X -> 3.9.0 (October, 2020) |

New features and optimizations were added in this release, e.g., string methods to remove prefixes and suffixes ( |

Patch |

3.9.5 -> 3.9.6 (June, 2021) |

This release contained bug and maintenance fixes, e.g., a confusing error message was updated in the |

7.2. Version bumping#

While we’ll discuss the full workflow for releasing a new version of your package in Section 7.3, we first want to discuss version bumping. That is, how to increment the version of your package when you’re preparing a new release. This can be done manually or automatically as we’ll show below.

7.2.1. Manual version bumping#

Once you’ve decided what the new version of your package will be (i.e., are you making a patch, minor, or major release) you need to update the package’s version number in your source code. For a poetry-managed project, that information is in the pyproject.toml file. Consider the pyproject.toml file of the pycounts package we developed in Chapter 3: How to package a Python, the top of which looks like this:

[tool.poetry]

name = "pycounts"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Calculate word counts in a text file!"

authors = ["Tomas Beuzen"]

license = "MIT"

readme = "README.md"

...rest of file hidden...

Imagine we wanted to make a patch release of our package. We could simply change the version number manually in this file to “0.1.1”, and many developers do take this manual approach. An alternative method is to use the poetry version command. The poetry version command can be used with the arguments patch, minor, or major depending on how you want to update the version of your package. For example, to make a patch release, we could run the following at the command line:

Tip

If you’re building the pycounts package with us in this book, you don’t have to run the below command, it is just for demonstration purposes. We’ll make a new version of pycounts later in this chapter.

$ poetry version patch

Bumping version from 0.1.0 to 0.1.1

This command changes the version variable in the pyproject.toml file:

[tool.poetry]

name = "pycounts"

version = "0.1.1"

description = "Calculate word counts in a text file!"

authors = ["Tomas Beuzen"]

license = "MIT"

readme = "README.md"

...rest of file hidden...

7.2.2. Automatic version bumping#

In this book, we’re interested in automating as much as possible of the packaging workflow. While the manual versioning approach described above in Section 7.2.1 is certainly used by many developers, we can do things more efficiently! To automate version bumping, you’ll need to be using a version control system like Git. If you are not using version control for your package, you can skip to Section 7.3.

Python Semantic Release (PSR) is a tool that can automatically bump version numbers based on keywords it finds in commit messages. The idea is to use a standardized commit message format and syntax, which PSR can parse to determine how to increment the version number. The default commit message format used by PSR is the Angular commit style, which looks like this:

<type>(optional scope): short summary in present tense

(optional body: explains motivation for the change)

(optional footer: note BREAKING CHANGES here, and issues to be closed)

<type> refers to the kind of change made and is usually one of:

feat: A new feature.fix: A bug fix.docs: Documentation changes.style: Changes that do not affect the meaning of the code (white-space, formatting, missing semi-colons, etc).refactor: A code change that neither fixes a bug nor adds a feature.perf: A code change that improves performance.test: Changes to the test framework.build: Changes to the build process or tools.

scope is an optional keyword that provides context for where the change was made. It can be anything relevant to your package or development workflow (e.g., it could be the module or function name affected by the change).

Different text in the commit message will trigger PSR to make different kinds of releases:

A

<type>offixtriggers a patch version bump, e.g.:$ git commit -m "fix(mod_plotting): fix confusing error message in \ plot_words"A

<type>offeattriggers a minor version bump, e.g.:$ git commit -m "feat(package): add example data and new module to \ package"The text

BREAKING CHANGE:in thefooterwill trigger a major release, e.g.:$ git commit -m "feat(mod_plotting): move code from plotting module \ to pycounts module $ $ BREAKING CHANGE: plotting module wont exist after this release."

To use PSR we need to install and configure it. To install PSR as a development dependency of a poetry-managed project, you can use the following command:

$ poetry add --group dev python-semantic-release --python "^3.12"

Attention

Adding python-semantic-release is a great example of why upper caps on dependency versions can be a pain, as we discussed in Section 3.6.1. At the time of writing, one of the dependencies of python-semantic-release, click-option-group, has an upper cap of <4.0 on the Python version it requires (see the source code), so it’s not compatible with our package which supports Python >=3.12. Thus, unless click-option-group removes this upper cap, the easiest way for us to add python-semantic-release is to tell poetry to only install it for Python versions ^3.12 (i.e., >=3.12 and <4.0), by using the argument --python "^3.12".

To configure PSR, we need to tell it where the version number of our package is stored. The package version is stored in the pyproject.toml file for a poetry-managed project. It exists as the variable version under the table [tool.poetry]. To tell PSR this, we need to add a new table to the pyproject.toml file called [tool.semantic_release] within which we specify that our version_variable is stored at pyproject.toml:version:

...rest of file hidden...

[tool.semantic_release]

version_toml = [

"pyproject.toml:tool.poetry.version",

]

Finally, you can use the command semantic-release version at the command line to get PSR to automatically bump your package’s version number. PSR will parse all the commit messages since the last tag of your package to determine what kind of version bump to make. For example, imagine the following three commit messages have been made since tag v0.1.0:

1. "fix(mod_plotting): raise TypeError in plot_words"

2. "fix(mod_plotting): fix confusing error message in plot_words"

3. "feat(package): add example data and new module to package"

PSR will note that there are two “fix” and one “feat” keywords. “fix” triggers a patch release, but “feat” triggers a minor release, which trumps a patch release, so PSR would make a minor version bump from v0.1.0 to v0.2.0.

As a more practical demonstration of how PSR works, imagine we have a package at version 0.1.0, make a bug fix and commit our changes with the following message:

Tip

If you’re building the pycounts package with us in this book, you don’t have to run the below commands, they are just for demonstration purposes. We’ll make a new version of pycounts later in this chapter.

$ git add src/pycounts/plotting.py

$ git commit -m "fix(code): change confusing error message in \

plotting.plot_words"

We then run semantic-release version to update our version number. In the command below, we’ll specify the argument -vv to ask PSR to print extra information to the screen so we can get an inside look at how PSR works and --noop to make it a “dry run” (i.e., PSR won’t actually change anything in our project):

$ semantic-release -vv --noop version

Creating new version

debug: get_current_version_by_config_file()

debug: Parsing current version: path=PosixPath('pyproject.toml')

debug: Regex matched version: 0.1.0

debug: get_current_version_by_config_file -> 0.1.0

Current version: 0.1.0

debug: evaluate_version_bump('0.1.0', None)

debug: parse_commit_message('fix(code): change confusing error... )

debug: parse_commit_message -> ParsedCommit(bump=1, type='fix')

debug: Commits found since last release: 1

debug: evaluate_version_bump -> patch

debug: get_new_version('0.1.0', 'patch')

debug: get_new_version -> 0.1.1

debug: set_new_version('0.1.1')

debug: Writing new version number: path=PosixPath('pyproject.toml')

debug: set_new_version -> True

debug: commit_new_version('0.1.1')

debug: commit_new_version -> [main d82fa3f] 0.1.1

debug: Author: semantic-release <semantic-release>

debug: 1 file changed, 5 insertions(+), 1 deletion(-)

debug: tag_new_version('0.1.1')

debug: tag_new_version ->

Bumping with a patch version to 0.1.1

We can see that PSR found our commit messages, and decided that a patch release was necessary based on the text in the message. We can also see that command automatically updated the version number in the the pyproject.toml file and created a new version control tag for our package’s source (we talked about tags in Section 3.9). In the next section, we’ll go through a real example of using PSR with our pycounts package.

7.3. Checklist for releasing a new package version#

Now that we know about versioning and how to increment the version of our package, we’re ready to run through a release checklist. We’ll make a new minor release of the pycounts package we’ve been developing throughout this book, from v0.1.0 to v0.2.0, to demonstrate each step in the release checklist.

7.3.1. Step 1: make changes to package source files#

This is an obvious one, but before you can make a new release, you need to make the changes to your package’s source that will comprise your new release!

Consider our pycounts package. We published the first release, v0.1.0, of our package in Chapter 3: How to package a Python. Since then, we’ve made a few changes. Specifically:

In Chapter 4: Package structure and distribution, we added a new “datasets” module to our package along with some example data, a text file of the novel Flatland by Edwin Abbott8, that users could load to try out the functionality of our package.

In Chapter 5: Testing, we significantly upgraded our testing suite by adding several new unit, integration, and regression tests to the

tests/test_pycounts.pyfile.

Tip

In practice, if you’re using version control, changes are usually made to a package’s source using branches. Branches isolate your changes so you can develop your package without affecting the existing, stable version. Only when you’re happy with your changes do you merge them into the existing source.

7.3.2. Step 2: document your changes#

Before we make our new release, we should document everything we’ve changed in our changelog. For example, here’s pycounts’s updated CHANGELOG.md file:

Tip

We talked about changelog file format and content in Section 6.2.5.

# Changelog

<!--next-version-placeholder-->

## v0.2.0 (10/09/2024)

### Feature

- Added new datasets modules to load example data

### Fix

- Check type of argument passed to `plotting.plot_words()`

### Tests

- Added new tests to all package modules in test_pycounts.py

## v0.1.0 (24/08/2024)

- First release of `pycounts`

If using version control, you should commit this change to make sure it becomes part of your release:

$ git add CHANGELOG.md

$ git commit -m "build: preparing for release v0.2.0"

$ git push

7.3.3. Step 3: bump version number#

Once your changes for the new release are ready, you need to bump the package version manually (Section 7.2.1) or automatically with the PSR tool (Section 7.2.2).

We’ll take the automatic route using PSR here, but if you’re not using Git as a version control system, you’ll need to do this step manually. The changes we made to pycounts, described in the section above, constitute a minor release (we added a new feature to load example data and made some significant changes to our package’s test framework). When we committed these changes in Section 4.4 and Section 5.6, we did so with the following collection of commit messages:

$ git commit -m "feat: add example data and datasets module"

$ git commit -m "test: add additional tests for all modules"

$ git commit -m "fix: check input type to plot_words function"

As we discussed in Section 7.2.2, PSR can automatically parse these commit messages to increment our package version for us. If you haven’t already, install PSR as a development dependency using poetry:

Attention

If you’re following on from Chapter 3: How to package a Python and created a virtual environment for your pycounts package using conda, as we did in Section 3.5.1, be sure to activate that environment before continuing by running conda activate pycounts at the command line.

$ poetry add --group dev python-semantic-release --python "^3.12"

This command updated our recorded package dependencies in pyproject.toml and poetry.lock, so we should commit those changes to version control before we update our package version:

$ git add pyproject.toml poetry.lock

$ git commit -m "build: add PSR as dev dependency"

$ git push

Now we can use PSR to automatically bump our package version with the semantic-release version command. If you want to see exactly what PSR found in your commit messages and why it decided to make a patch, minor, or major release, you can add the argument -v DEBUG.

Attention

Recall from Section 7.2.2 that to use PSR, you need to tell it where your package’s version number is stored by defining version_toml = ["pyproject.toml:tool.poetry.version",] under the [tool.semantic_release] table in pyproject.toml.

We are also using the --no-push and --no-changelog arguments to stop PSR from automatically pushing changes to our GitHub repository (we’ll do this ourselves manually) or make any changes to our CHANGELOG (we did this ourselves earlier). We’ll talk more about using these helpful automated functions in Chapter 8: Continuous integration and deployment.

$ semantic-release version --no-push --no-changelog

Creating new version

Current version: 0.1.0

Bumping with a minor version to 0.2.0

This step automatically updated our package’s version in the pyproject.toml file and created a new tag for our package, “v0.2.0”, which you could view by typing git tag --list at the command line:

$ git tag --list

v0.1.0

v0.2.0

7.3.4. Step 4: run tests and build documentation#

We’ve now prepped our package for release, but before we release it, it’s important to check that its tests run and documentation builds successfully. To do this with our pycounts package, we should first install the package (we should re-install because we’ve created a new version):

$ poetry install

Installing the current project: pycounts (0.2.0)

Now we’ll check that our tests are still passing and what their coverage is using pytest and pytest-cov (we discussed these tools in Chapter 5: Testing):

$ pytest tests/ --cov=pycounts

========================= test session starts =========================

Name Stmts Miss Cover

---------------------------------------------------

src/pycounts/__init__.py 2 0 100%

src/pycounts/data/__init__.py 0 0 100%

src/pycounts/datasets.py 5 0 100%

src/pycounts/plotting.py 12 0 100%

src/pycounts/pycounts.py 16 0 100%

---------------------------------------------------

TOTAL 35 0 100%

========================== 7 passed in 0.41s ==========================

Finally, to check that documentation still builds correctly you typically want to create the documentation from scratch, i.e., remove any existing built documentation in your package and then building it again. To do this, we first need to run make clean before running make html from the docs/ directory (we discussed building documentation with these commands in Chapter 6: Documentation). In the spirit of efficiency we can combine these two commands together like we do below:

$ cd docs

$ make clean html

Running Sphinx

...

build succeeded.

The HTML pages are in _build/html.

Looks like everything is working!

7.3.5. Step 5: tag a release with version control#

For those using remote version control on GitHub (or similar), it’s time to tag a new release of your repository on GitHub. If you’re not using version control, you can skip to the next section. We discussed how to tag a release and why we do this in Section 3.9. Recall that it’s a two-step process:

Create a tag marking a specific point in a repository’s history using the command

git tag.On GitHub, create a release of your repository based on the tag.

If using PSR to bump your package version, then step 1 was done automatically for you. If you didn’t use PSR, you can make a tag manually using the following command:

$ git tag v0.2.0

You can now push any local commits and your new tag to GitHub with the following commands:

$ git push

$ git push --tags

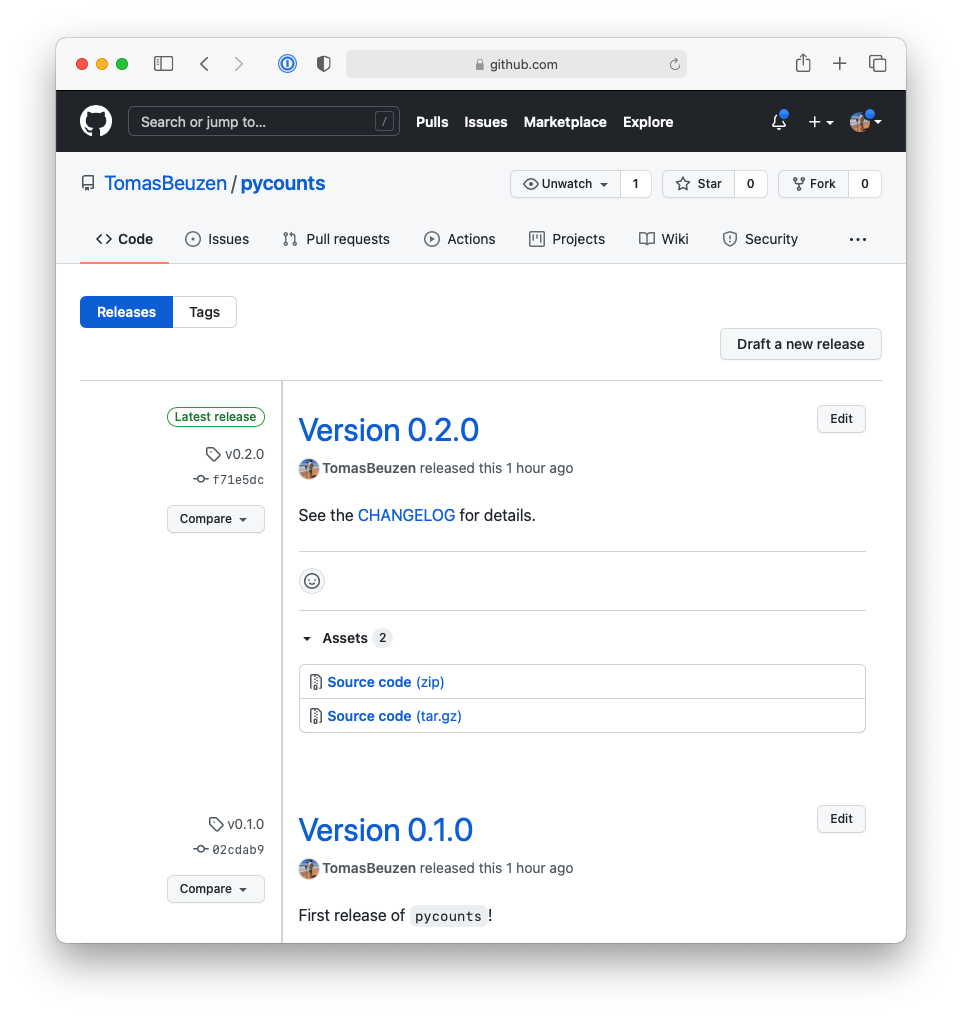

After running those commands for our pycounts package, we can go to GitHub and navigate to the “Releases” tab to see our tag, as shown in Fig. 7.1.

Fig. 7.1 Tag of v0.2.0 of pycounts on GitHub.#

To create a release from this tag, click “Draft a new release”. You can then identify the tag from which to create the release and optionally add a description of the release; often, this description links to the changelog, where changes have already been documented. Fig. 7.2 shows the release of v0.2.0 of pycounts on GitHub.

Fig. 7.2 Release v0.2.0 of pycounts on GitHub.#

7.3.6. Step 6: build and release package to PyPI#

It’s now time to build the new distributions for our package (i.e., the sdist and wheel — we talked about these in Section 4.3). We can do that with poetry using the following command run from the root package directory:

$ poetry build

Building pycounts (0.2.0)

- Building sdist

- Built pycounts-0.2.0.tar.gz

- Building wheel

- Built pycounts-0.2.0-py3-none-any.whl

You can now use and share these distributions as you please, but most developers will want to upload them to PyPI, which is what we’ll do here.

As discussed in Section 3.10.2, it’s good practice to release your package on TestPyPI before PyPI, to test that everything is working as expected. We can do that with poetry publish:

$ poetry publish -r test-pypi

Attention

The above command assumes that you have added TestPyPI to the list of repositories poetry knows about via: poetry config repositories.test-pypi https://test.pypi.org/legacy/

Now you should be able to download your package from TestPyPI:

$ pip install --index-url https://test.pypi.org/simple/ \

--extra-index-url https://pypi.org/simple pycounts

Note

By default pip will search PyPI for the named package. The argument --index-url points pip to the TestPyPI index instead. If your package has dependencies that are not on TestPyPI, you may need to tell pip to also search PyPI with the following argument: --extra-index-url https://pypi.org/simple.

If you’re happy with how your newly versioned package is working, you can go ahead and publish to PyPI:

$ poetry publish

7.4. Automating releases#

As you’ve seen in this chapter, there are quite a few steps to go through in order to make a new release of a package. In Chapter 8: Continuous integration and deployment we’ll see how we can automate the entire release process, including running tests, building documentation, and publishing to TestPyPI and PyPI.

7.5. Breaking changes and deprecating package functionality#

As discussed earlier in the chapter, major version releases may come with backward incompatible changes, which we call “breaking changes”. Breaking changes affect your package’s user base. The impact and importance of breaking changes is directly proportional to the number of people using your package. That’s not to say that you should avoid breaking changes — there are good reasons for making them, such as improving software design mistakes, improving functionality, or making code simpler and easier to use.

If you do need to make a breaking change, it is best to implement that change gradually, by providing adequate warning and advice to your package’s user base through “deprecation warnings”.

We can add a deprecation warning to our code by using the warnings module from the Python standard library. For example, imagine that we want to remove the get_flatland() function from the datasets module of our pycounts package in the upcoming major v1.0.0 release. We can do this by adding a FutureWarning to our code, as shown in the datasets.py module below (we created this module back in Section 4.2.6).

Tip

If you’ve used any larger Python libraries before (such as NumPy, Pandas or scikit-learn) you probably have seen deprecation warnings before! On that note, these large, established Python libraries offer great resources for learning how to properly manage your own package — don’t be afraid to check out their source code and history on GitHub.

from importlib import resources

import warnings

def get_flatland():

"""Get path to example "Flatland" [1]_ text file.

...rest of docstring hidden...

"""

warnings.warn("This function will be deprecated in v1.0.0.",

FutureWarning)

with resources.path("pycounts.data", "flatland.txt") as f:

data_file_path = f

return data_file_path

If we were to try and use this function now, we would see the FutureWarning printed to our output:

>>> from pycounts.datasets import get_flatland

>>> flatland_path = get_flatland()

FutureWarning: This function will be deprecated in v1.0.0.

A few other things to think about when making breaking changes:

If you’re changing a function significantly, consider keeping both the legacy version (with a deprecation warning) and new version of the function for a few releases to help users make a smoother transition to using the new function.

If you’re deprecating a lot of code, consider doing it in small increments over multiple releases.

If your breaking change is a result of one of your package’s dependencies changing, it is often better to warn your users that they require a newer version of a dependency rather than immediately making it a required dependency of your package.

Documentation is key! Don’t be afraid to be verbose about documenting breaking changes in your package’s documentation and changelog.

7.6. Updating dependency versions#

If your package depends on other packages, like our pycounts package does, you’ll need to think about updating your dependency version constraints as new versions of dependencies are released over time. This is true even for the version(s) of Python that your package supports.

Luckily, poetry makes this a relatively simple process. The command poetry update can be used to update the version of installed dependencies in your virtual environment, within the constraints of the pyproject.toml file. This is useful for testing that your package works as expected with newer versions of its dependencies. For example, if we wanted to install the latest version of matplotlib compatible with our pycounts package, we could use the following code:

$ poetry update matplotlib

However, poetry update won’t update the constraints specified in your pyproject.toml file, or the metadata built into your package releases. To update that you have two options:

Manually modify version constraints in

pyproject.toml.Use

poetry addto update a dependency to a specific version(s).

For example, our current version constraint for matplotlib is shown in pyproject.toml:

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = ">=3.12"

matplotlib = ">=3.10.0"

If we wanted the minimum version of matplotlib to instead be 3.11.0, we could manually adjust our pyproject.toml file as shown below:

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = ">=3.12"

matplotlib = ">=3.11.0"

Or we could run the following code:

$ poetry add "matplotlib>=3.11.0"

Note

We use double quotes in the command above because in many shells, like bash, > is a redirection operator. The double quotes are used to preserve the literal value of the contained characters (read more in the documentation).